The Lynching of Leo Frank

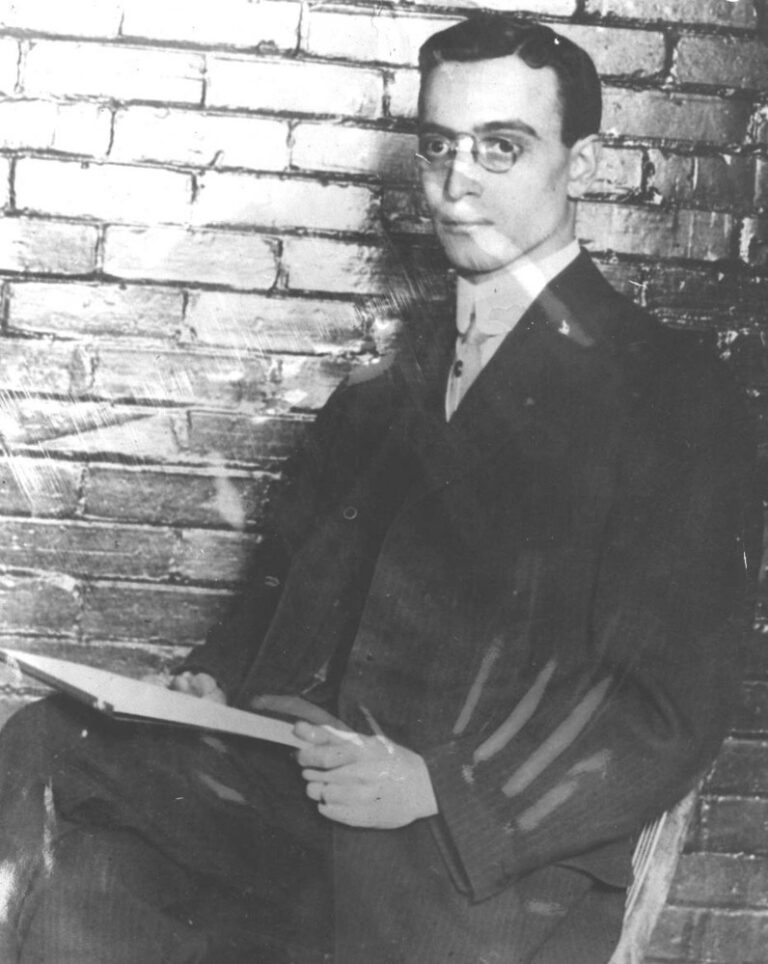

On Confederate Memorial Day, April 26,1913, thirteen-year-old Mary Anne Phagan was found murdered in the basement of the National Pencil Company in Atlanta, Georgia. The twenty-nine-year-old Jewish superintendent of the factory, Leo M. Frank, was arrested for the crime. The events that followed one of the most sensational trials of the century – Frank’s conviction, the commutation of his death sentence and his subsequent lynching – polarized Atlanta. It captured the attention and sympathies of national and international audiences, and launched far-reaching social, legal and cultural changes.

The question remains, was justice served?

Leo Frank received justice in that he had a trial before a jury. But were the trial proceedings just? Was justice derailed when both his sentence to hang and its commutation to life imprisonment by Georgia’s governor were overthrown by a vigilante lynch mob? If, as Governor John M. Slaton and many others believed, there was reasonable doubt about Frank’s guilt and that he might have been falsely accused before a court of law, then someone else murdered Mary Phagan. If that is the case, then the true killer was never punished.

Historical Context for the Leo Frank Case

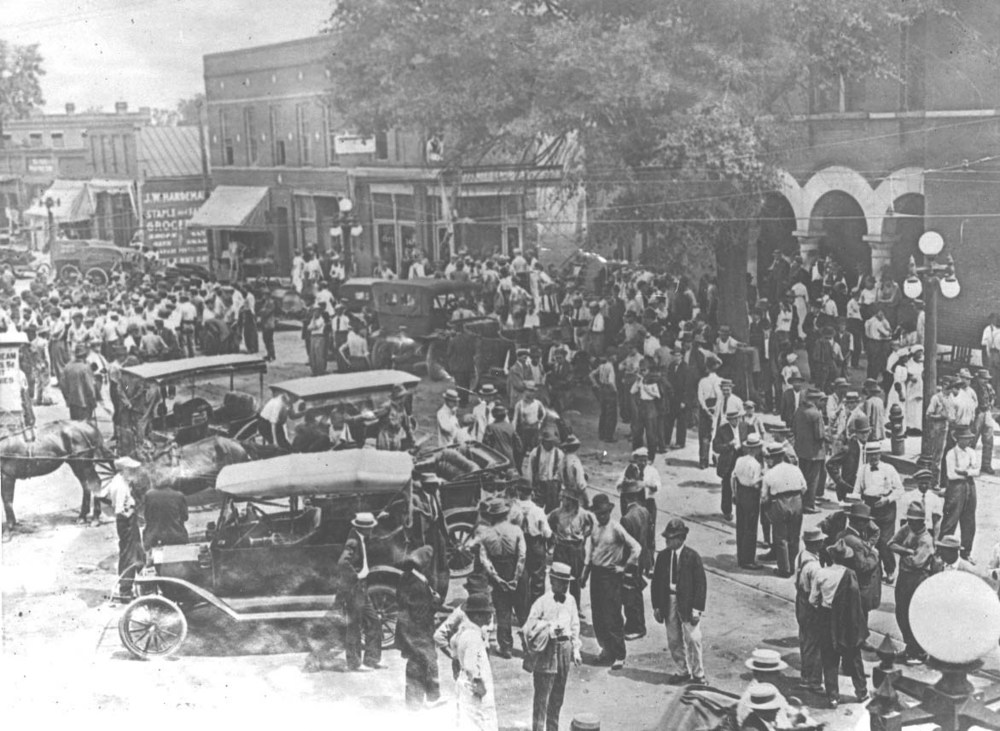

By the late 1930s, in the far West and Midwest, lynchings claimed victims who were white, Mexican, American Indian, Asian and African American. In the South, the victims were largely black. Most lynchings were spontaneous; the victims were never tried in a court of law. They were public spectacles; the faces of members of the lynch party and the crowd were captured in photographs.

Yet none of these lynchings has been the subject of dozens of books, four movies and a Broadway play: rather, it is the lynching of one Jewish white man that has captured so much attention.

The Vision of the New South: The Civil War left the South’s economy in ruins, its male population diminished by death or injury, its social order forever changed by the abolition of slavery. The vision of a “New South” imagined a new industrial age that would increase opportunity for families, including women and children, by moving them from an agrarian society and into the work force in newly industrialized cities like Atlanta – a society where blacks and whites would live together in harmony.

Cotton States and International Exposition: The 1895 Exposition, the embodiment of the New South vision and the biggest fair of the nineteenth century, was intended to be the region’s “coming out party”. Held in Piedmont Park, the fair boasted 6,000 exhibits and thirteen main structures. The only surviving features of the fair are the granite steps and stone balustrades scattered around the park that once led to major buildings built for the Exposition and Lake Clara Meer.

The Reality of the New South and Race Relations: By the early twentieth century, the vision of the New South was largely unrealized and its social, economic and political tensions had strong bearing on the investigation into Mary Phagan’s murder, Leo Frank’s trial and its aftermath. Industrialization and urbanization led to a declining agricultural economy. Rural families were uprooted, and women and children entered the workplace. Entrenched white supremacy, rigid segregation, vigilantism and mob violence were widespread.

Northerners and immigrants, some of whom were Jews, were blamed for the region’s dramatic and tumultuous societal changes.

In 1906, an ugly gubernatorial campaign between Hoke Smith and Clark Howell was aimed at disenfranchising African American voters. Exaggerated reports of attacks on white women by black men enflamed the city. On September 22, a violent race riot erupted and lasted for several days seriously eroding already fragile race relations.

The same tensions and societal struggles were pervasive throughout the United States: the disparity in living conditions between the “haves” and the “have-nots”; the lack of protection for women and children in the work force; the growing resentment toward immigrants from eastern and southern Europe; labor unrest and the strained state of race relations.

All these factors and forces came into play on the morning of April 27, 1913 with the discovery of Mary Phagan’s battered body in the basement of the National Pencil Company in Atlanta.

The Crime and the Arrest

Saturday, April 26, 1913 was Confederate Memorial Day. Thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan was one of one hundred or so young girls and women who worked at the pencil company. She stopped by the factory to pick up her pay from the superintendent, Leo Frank.

Her body was discovered by night watchman Newt Lee in the National Pencil Company’s basement. Lee called the police who observed a young girl’s body so covered in soot that they had trouble ascertaining that the victim was white.

Two handwritten notes lay near the body and referred to “a long tall black negro.” Lee, who fit the description, was arrested for the crime.

Police drove Leo Frank to the funeral home to identify the body. Over the next several days, police questioned several factory employees, but then turned their attention to Frank, the last person to see Mary alive. Later that day, Frank was arrested.

On May 23, the Grand Jury convened to decide whether to charge Leo Frank with murder. Fulton County Solicitor General, Hugh Manson Dorsey, presented little evidence but contended that Frank indeed murdered Mary Phagan. The next day, after five minutes of deliberation, the Grand Jury indicted Frank for the murder and he was transferred to the Fulton County Jail.

Days later, following a tip, police turned their attention to Jim Conley, the pencil company’s black sweeper. When initially questioned as the suspected author of the “murder notes” found near the body, he claimed he could neither read nor write. That was disputed by Leo Frank who knew Conley was literate. Intense questioning by police and a comparison of Conley’s signature to the notes confirmed that he wrote them.

The Trial

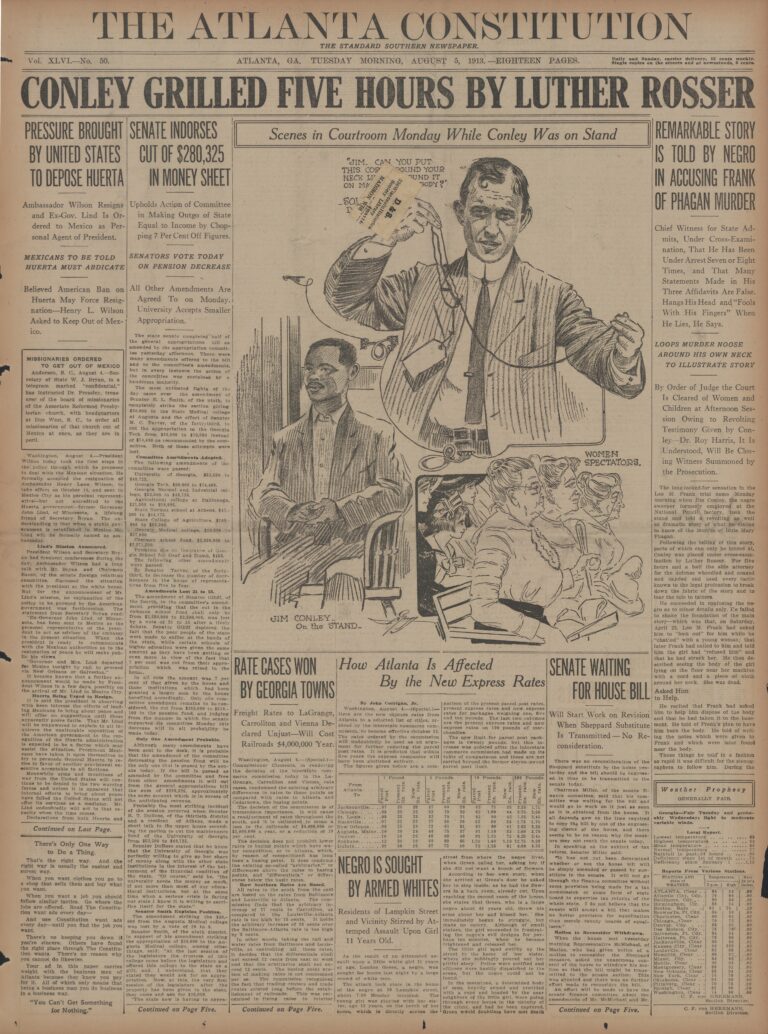

On July 28, 1913, the trial of Leo Frank began. The presiding judge was Leonard Roan. Hugh Dorsey was the prosecuting attorney and Frank’s legal team was led by Luther Rosser and co-counsel Reuben Arnold. An all-male white jury was selected.

The prosecution’s theory was that Frank was the murderer, and that the “murder notes” had been dictated by Frank to Conley in an effort to pin the crime on Newt Lee. Dorsey planned to establish that Frank often used Conley in concealing his pursuit of young women in his employ.

The defense’s theory was that Conley was the murderer. The team hoped to prove that Frank’s schedule the day of the murder made it impossible for him to commit the crime; that he had no relationship with the murder victim and that he did not pursue girls in his employ. Most importantly, they sought to discredit Jim Conley.

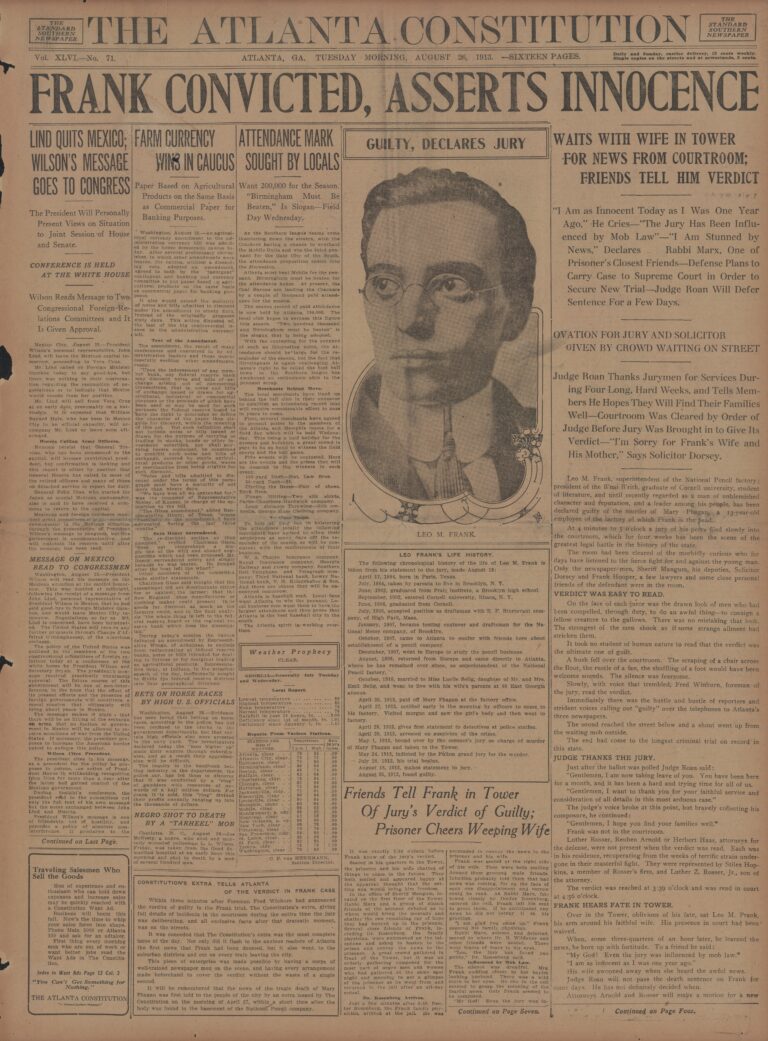

During the trial, public sentiment turned against Frank. Charging that jurors were intimidated by the hostility inside and outside of the courtroom, the defense asked for but was denied a mistrial. Fearing violence if there were an acquittal, Judge Roan brokered a deal in which neither the defendant nor his lawyers would be present when the verdict was read.

On August 25, it took the jury an hour and forty-five minutes to convict Frank of murder. The following day, Roan sentenced Frank to death by hanging. The sentence was scheduled to be carried out on October 10, 1913.

The Appeals

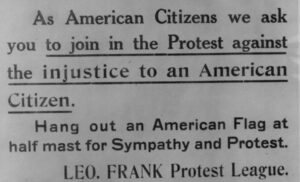

By April of 1915, Frank’s defense team, discouraged following successive defeats of their appeals in the Georgia courts, was encouraged by growing national support. The team, now led by Louis Marshall, made a final effort in an appeal to the United States Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus. Habeas corpus is a legal instrument used to bring someone who has been imprisoned before the court for a decision on whether that detention was legal. On April 19, the court denied Frank’s appeal in a 7-2 vote. At this point, Frank had spent two years in jail.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes and Justice Charles Evans Hughes dissented. Holmes wrote:

“Mob law does not become due process of law by securing the assent of a terrorized jury… I very seriously doubt if the petitioner…has had due process of law…because of the trial taking place in the presence of a hostile demonstration and seemingly dangerous crowd, thought by the presiding Judge to be ready for violence unless a verdict of guilty was rendered.”

In 1923, Holmes restated that argument in the case of five African Americans in Arkansas who, “…were hurried to conviction under the pressure of a mob, without any regard for their rights, and without according to them due process of law.” Holmes’ opinion is now accepted legal precedent.

The Remaining Option

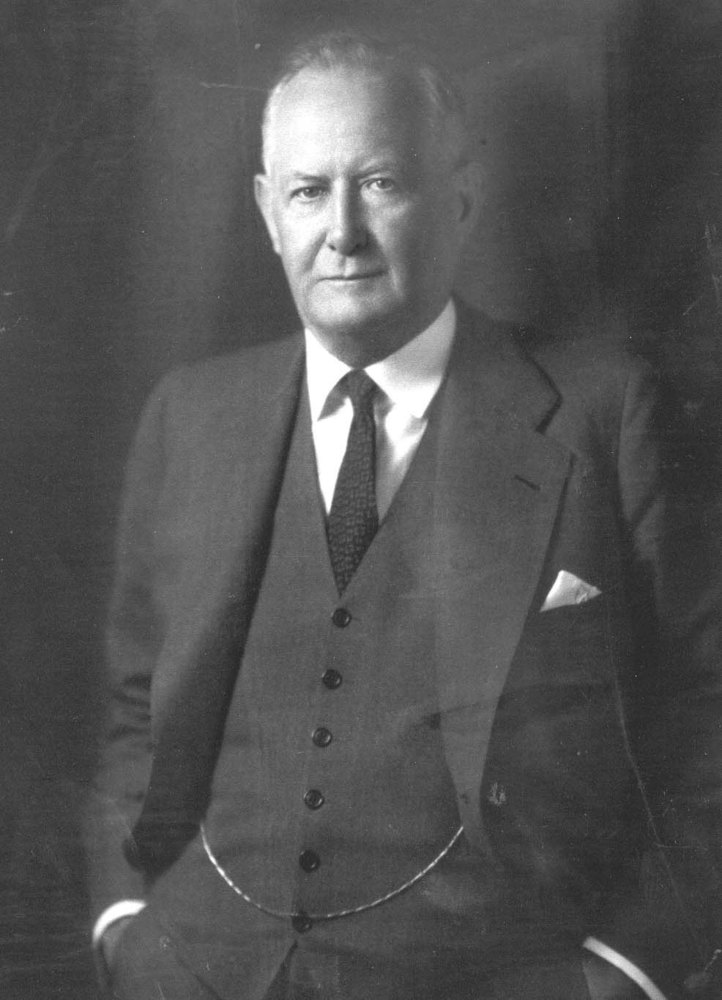

With no avenues left in the courts, the defense asked the Pardons and Paroles Board of the Georgia Prison Commission to recommend clemency for Frank to departing Georgia Governor John M. Slaton. The Commission denied the defense’s request and recommended that the death sentence stand.

At a final hearing on the case before the governor, inconsistencies in Conley’s testimony came to light. Slaton, after pouring over more than 10,000 pages of documents and carefully examining new evidence, commuted Frank’s death sentence to life in prison. Before announcing his decision, Slaton, fearing for Frank’s safety, had him transferred to the state prison farm in Milledgeville, Georgia.

Tom Watson, a former Populist politician and journalist, launched a vicious antisemetic campaign in his Jeffersonian newspaper urging the lynchings of both Frank and Slaton, “…Jew money has debased us, bought us, and sold us…and laughs at us…Hereafter let no man reproach the South with Lynch law…let him say whether lynch law is not better than no law at all.”

Slaton, once beloved, called the National Guard to protect himself as 4,000 citizens hung him in effigy outside the governor’s mansion.

The State Prison Farm, Milledgeville, Georgia and Lynching

Soon after Frank was moved to the state prison, a group of leading citizens from Marietta in Cobb County close to Mary Phagan’s hometown conspired to formulate a plan to deliver the justice they felt had been denied. Politically well-connected, financially secure and socially prominent, the conspirators included a solicitor general, a state legislator, a former Georgia governor, a businessman, a judge and a Confederate veteran and attorney.

The Prison officials had been paid off to look the other way. On August 16, 1915, a lynch party seized Frank and drove him four hours to a large oak tree at Frey’s Gin, two miles from Marietta. Frank was hanged at 7:05am. Within ninety minutes, a crowd of 1,000 onlookers gathered. Afterward, the lynchers covered up their actions-no one was arrested or prosecuted for the crime.

The Aftermath

Atlanta newspapers and those throughout Georgia condemned the lynching. National papers decried it as well, but also denounced the culture in Georgia and the entire South. Tom Watson’s Jeffersonian stepped up its inflammatory rhetoric about Frank, Slaton, Jewish leaders and Jews in general.

On September 2, 1915, Watson called for a revival of the Ku Klux Klan, a hooded fraternity of horsemen that had disbanded in 1869 and whose midnight rides, cross-burnings and ferocious attacks against African Americans had terrorized the South. Watson’s call was answered on November 13, 1915 at the top of Stone Mountain outside of Atlanta. A group of men lighted a giant pitch-and-kerosene-soaked wooden cross signaling the return of the organization that had first been established by Confederate veterans to protect “the southern way of life” in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Some national Jewish community leaders took on the Frank case as a rallying cry. The Anti-Defamation League, founded to “… stop, by appeals to reason and conscience, and if necessary, by appeals to law, the defamation of the Jewish people.”, was galvanized by the injustice it felt was perpetrated and grew in membership and significance.

No one was ever connected to or charged with the murder of Leo Frank.

In 1982, the Frank case was back in the news. Eighty-three-year-old Alonzo Mann, Frank’s former office boy, asserted that he had seen Jim Conley carrying the body of Mary Phagan. Mann, who was fourteen at the time, said Conley threatened to kill him if he ever revealed what he saw. Terrified, Mann kept the secret for sixty-nine years.

Attorneys Charles Wittenstein of the Anti-Defamation League and Dale Schwartz petitioned the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles for a posthumous pardon for Frank. In 1986, after rejecting the initial request, the Board, while not addressing the question of guilt or innocence, granted a pardon based on the State’s failure to protect Frank from the hands of the lynchers.

You can find the digitized Leo M. Frank Collection in the Digital Library of Georgia

Browse Our Archives

Browse our collection of over 20,000 artifacts, textiles, photographs, and vertical files covering more than a century of Jewish life in the South.

Plan Your Visit

One of the leading destinations in Atlanta, GA, our Jewish culture, arts and history museum is home to the permanent exhibition Absence of Humanity: The Holocaust Years, 1933-1945; the Blonder Family Gallery hosts History with Chutzpah: Remarkable Stories of the Southern Jewish Experience; and the Schwartz Gallery, which hosts a variety of traveling and rotating exhibitions.