Stories of the Holocaust

Resilience runs deep.

Our approach to Holocaust education includes highlighting deeply personal stories of extraordinary people, many of whom survived and made new, prosperous lives in Atlanta. These stories that we collect, preserve, and share are instrumental in educating people across the Southeast through a host of immersive experiences, including guided tours of our Holocaust exhibit, advanced training through our Summer Teacher Institute, and story-sharing with Holocaust survivors. Our hope is that people of all ages can learn about—and find a personal connection with—one of humanity’s most significant moments in time.

Herbert Kohn

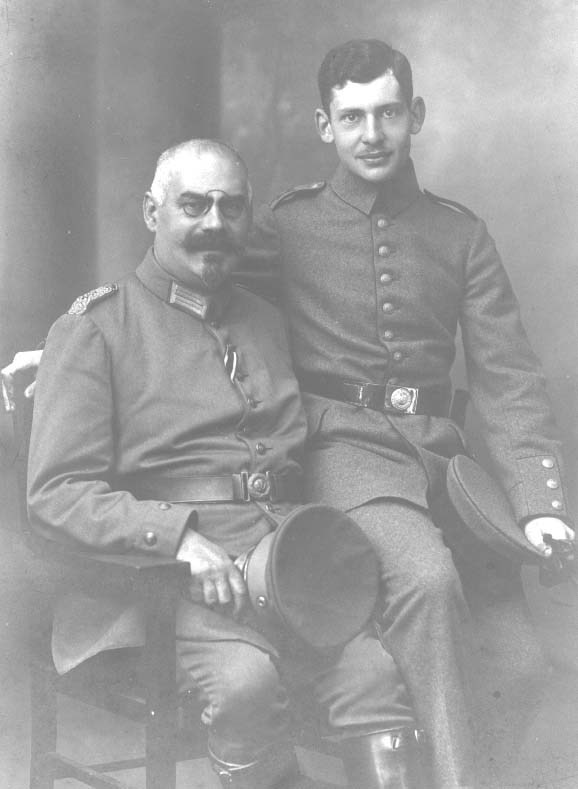

Herbert Kohn was born on September 27, 1926 in Frankfurt, Germany. His family had lived in the country for 450 years. Herbert’s father and both grandfathers fought for Germany during the first World War.

Schooling and Removal from Public School

Herbert began attending German public school in first grade at the age of six in 1932. He and the other children on his block would walk to and from school together every day. Three weeks after Hitler came to power in 1933 Herbert arrived at school only to have his teacher ask, “Are there any Jews in this room?” Herbert and one other student proudly raised their hands high. The teacher told them to go home: Jews were no longer allowed in public schools. This was the moment that Herbert realized everything had changed. He, for the first time in his life, walked home from school alone. The next day the same children who had always been his friends said to him, “What are you doing you damn Jew?” Their neighbors stopped speaking to them for fear of punishment or being fired from their jobs, and everything in Germany became segregated.

Herbert began attending a private school which had only Jewish students, teachers, and staff, including his father. The Kohn family thought this was only temporary, but once the Nuremberg Laws were passed (1935), they realized they needed to leave. They began writing to family all over the world. Distant family members in Mobile, Alabama sent them an affidavit which allowed the Kohn’s to receive a visa in 1938 to enter the United States, but due to immigration quotas the family would not be allowed to leave Germany that year.

Kristallnacht and Leo Kohn’s Arrival and Release from Buchenwald

On November 9, 1938 – Kristallnacht – stormtroopers, Nazi SA, came to the Kohn house. The soldier forced his way into the house, knocking Herbert’s mother to the floor, and demanded

that any Jewish men between the age of 16 and 60 come out. Leo Kohn (38) was forced to go with the stormtrooper.

No one knew where Herbert’s father went, but his mother decided instantly that if he ever returned, Leo needed to leave Germany immediately. She contacted a distant relative in London, England trying to get a transit visa for Leo. The relative sent a telegram back which stated that he would provide £2 a week for Leo. Herbert’s mother brought the telegram to the English consul in Frankfurt who stamped not only Leo’s passport but the passports of the entire Kohn family with visas to England.

Three and a half weeks later Herbert opened the door to see his father, who was almost unrecognizable: Leo had lost 30lbs and his hair had turned white. Though he had been instructed by the Nazis never to tell anyone what had happened to him, he recounted his story to his family.

Leo, and all of the Jewish men ages 16 to 60 in the Frankfurt area, were taken to a police precinct then to a sports arena with no access to food, water, or bathrooms. After two and a half days they were taken on passenger trains, not cattle cars, to Buchenwald concentration camp. After three and a half weeks in the camp his father singled out of the morning formation because Nazi soldiers found a document in Leo’s personal belongings which awarded him a medal2 for his service as a front soldier in the German army during WWI. The Nazis could no longer abuse Leo after discovering that he had been honored by Hitler himself, so they took his uniform, gave him his raincoat back, and told him to go.

Leo left for London the morning after returning home. Leo’s brother, more immediately at risk of deportation due to his age, followed first; Herbert and his mother left for England in May 1939, where Herbert lived in a home for Jewish boys.

Arrival in America

In April 1940, the Kohn family boarded a cruise ship in Liverpool. After a 15 day journey the Kohn’s disembarked in New York where they were met by a relative of their sponsors (family members who lived in Atlanta, Georgia). They were given the choice to either establish themselves in New York or Chicago or come down South and learn to farm. The Kohns chose the latter, and moved to Demopolis, Alabama.

Penina Weisz Bowman

Penina Weisz was born on April 19, 1927 in Cluj, Romania. Her father ran the community mikveh (ritual bath), and she grew up in an observant Jewish family.

Deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau

In 1940 the area of Romania where Penina lived was annexed by Hungary, and increasing restrictions were placed on Jews until May of 1940 when all of the Jewish residents of Cluj were rounded up. Penina and her family marched for two weeks to an abandoned brick factory where they remained without any food except what they brought with them for over a week.

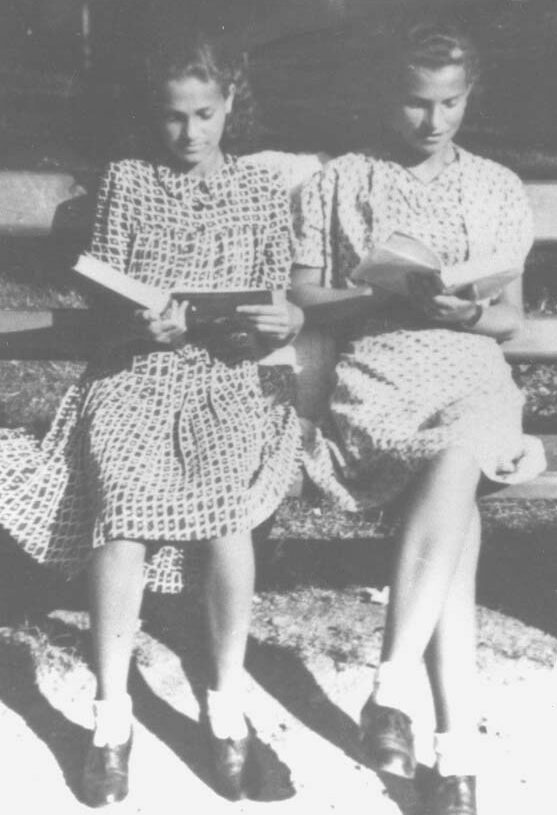

Penina and her family were then loaded into cattle cars and transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Penina’s brother and father were separated from the women. Penina’s mother was sent directly to the gas chambers, and Penina, her two sisters, and her aunt were sent to the barracks. After three months, Penina’s aunt was selected for the gas chambers. The Wiesz sisters realized that only the weak were being chosen in the selections so they avoided them. After six months they were told by a Hungarian overseer working in the camp who had taken a liking to them that that day’s selection was a good one so they went. She pointed out the sisters as being unafraid to work, and all three were selected to be transported to Mahrisch Weisswasser labor camp in Czechoslovakia.

DP Camps and Meeting Harold

They were liberated by the Soviet Army on May 8, 1945, and all three sisters traveled back to Cluj. Penina’s younger sister decided to stay in Cluj because she heard that her boyfriend from before the war survived. Penina and her older sister were Zionists who wanted to go to Israel, then called Palestine, and joined a group of 42 people between the ages of 15 and 22 who shared their dream of starting a kibbutz. They went from DP (displaced persons) camp to DP camp together, eventually ending up in Salzburg, where they reunited with their brother.

It was while she was in the DP camp in Salzburg that she met her future husband Harold Bowman in October 1945. Harold was an Jewish American soldier who had come to the DP camp to practice Hebrew with the Jewish refugees he heard were there. He and Penina began to date, first using an interpreter then later on their own once Harold had taught Penina Hebrew. Harold was forced to leave Salzburg in March 1946 to be discharged from the army, but before he left he gave Penina the mogen david necklace he got for his bar mitzvah and parachute silk that he told her to save for her wedding dress. This is how Penina discovered she was engaged.

Getting to Mandatory Palestine

Penina, Miriam, and the other people in their Zionist group went from Salzburg to Italy where they boarded a ship headed to Mandatory Palestine, but they would be intercepted by the British who rerouted them to Cyprus. They were not allowed to bring anything but small personal items, like photographs, so Penina hid her parachute fabric in the lining of her coat.

By then, Harold had gone to Mandatory Palestine to study at the Technion under the GI Bill. He knew that Penina was in Cyprus because they had been exchanging letters, and he watched the lists of prisoners sent from Cyprus to Mandatory Palestine to see if Penina’s name was on it. However, the day Penina arrived, he had tests and did not check the list. Penina was placed on a bus to transport her to Atlit where she would be interred by the British, but she managed to slip a note that said “I have arrived” to a young girl and told her to bring it to the Technion.

She and Harold were eventually reunited and were married in March of 1947. Penina wore a dress she handmade from the fabric Harold gifted her. They moved to Chicago, Illinois to live with Harold’s parents in October 1947, eventually having three children. Though Harold wished to return to Israel after its independence, Penina could not bring herself to return to a war zone. They would however, visit many times to see family who still lived there before Harold passed in 2008 and Penina in 2018.

Curiosity. Piqued.

Unforgettable Stories from the Holocaust. Our Bearing Witness page features videos of Holocaust survivors telling their remarkable stories.